"WHY NO INQUEST? DO IT NOW, DR. GERBER."

AN EDITORIAL

Why hasn't County Coroner Sam Gerber called an inquest into the Sheppard murder case? What restrains

him? Is the Sheppard murder

case any different from the countless other murder mysteries

where the coroner has turned to this traditional method of investigation? An

inquest empowers use of the subpoena. It

puts witnesses under oath. It makes possible the examination of every

possible witness, suspect, relative, records and papers available anywhere. It

puts the investigation itself into the record. And--what's

most important of all-it sometimes solves crimes. What good reason is there now

for Dr. Gerber to delay any longer the use of the inquest? The murder of

Marilyn Sheppard is a baffling crime. Thus far it appears to have stumped

everybody. It may never be solved. But, this community can never have a

clear conscience until every possible method is applied to its solution.

What, Coroner Gerber,

is the answer to the question-Why don't you call an inquest into this

murder?

Cleveland Press, July 21, 1954, Pg. 1

This editorial, and many others like it splashed across Page 1 of The

Cleveland Press after July 4, 1954 when the young, pregnant wife of a prominent

Bay Village doctor turned up murdered inside her Bay Village home. Written by

the editor of The Cleveland Press, Louise B. Seltzer as mainly editorials to

get things to happen when he felt that the Bay Village and Cleveland Police

Departments or County Coroner Samuel R. Gerber weren't doing enough to get

justice, Seltzer helped ruin any good chances of Dr. Samuel Sheppard ever

getting a fair trail.

An Overview of Murder

"My God, Spen, get over here quick! I

think they've killed Marilyn!"

|

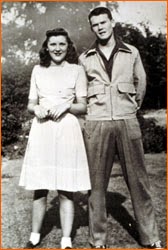

| Dr. and Mrs. Samuel Sheppard on their wedding day |

It was sometime during the early

hours of July 4, 1954 that prominent Bay View Hospital doctor Samuel Holmes

Sheppard's pretty four-month pregnant wife Marilyn Reese Sheppard was found

brutally murdered in her bed in the family's Bay Village home. Down the hall

from her room slept the couple's seven year old son Chip, as he was called, while

Marilyn's husband Sam slept on a day bed in the living room, having fallen

asleep earlier in the evening while he and Marilyn had entertained their friends

Don and Nancy Ahern.

On July 4, in the early morning

hours, Dr. Sheppard recalled that he was woken up by Marilyn crying out his

name several times. As he ran up the stairs to check on his wife (he assumed

that Marilyn was having a reaction similar to convulsions that she had had in

the early days of her pregnancy), he wound up being hit in the back of the head

and knocked out. When he gathered his senses, he was in a sitting position next

to the bed, his feet facing the hall. After checking on his wife and

determining that she was dead, he went and checked on his sleeping son. Hearing

a sound downstairs, he went downstairs and saw a form somewhere between the

front door towards the lake and the screen door. Following the figure, they

wound up down on the beach where Sam was again knocked unconscious. This time,

he came to by the tide washing up on him. Going back to the house, Sam again

claims that he checked again on Marilyn, for sure once, but possibly several times

before calling the first number that came to his mind-Mayor and Mrs.

Spencer

Houk. After they arrived, Mayor Houk called the police as well as Sam's

brothers Dr's. Richard and Steve Sheppard, who upon arriving at the house, took

Sam to their family hospital, Bay View, where Sam was treated for bruises on

the right side of his face, a swollen eye socket, two slightly chipped teeth,

slightly elevated blood pressure and for hypothermia.

|

| The Sheppard Doctors Richard A. (Father), Steve, Richard N and Sam |

|

| Dr. Samuel R. Gerber, MD Cuyahoga County Coroner |

At 7:50 AM on July 4, 1954,

Cuyahoga County Coroner Dr. Samuel R. Gerber, MD arrived on scene, and by 8:10,

Cleveland detective Michael Grabowski arrived on scene, per the request of both

Bay Village police department and Dr. Gerber. The crime scene was processed,

Sheppard was questioned both by detectives and Dr. Gerber at Bay View.

By 12:30 PM, Dr. Lester Adelson,

Deputy Coroner for Cuyahoga County began the autopsy of Marilyn Sheppard. It is

important to note, that unlike Dr. Gerber, who was trained as strictly a

physician and a lawyer; Dr. Adelson had

been trained as a pathologist, who

believed that "...in a murder case the body was the best witness. 'Unlike

a living witness, a victim's body does not shade the truth, tell lies, or plead

the Fifth Amendment.' he liked to say." 1 During autopsy,

Adelson determined that rigor mortis was complete, allowing him to place Marilyn's death somewhere between 4:15 and 4:45 AM. Her stomach was found empty,

and as a person needs five to seven hours to digest a large meal as the

Sheppard's and Ahern's had had the night before, this was very important. Also found during the autopsy

were fifteen crescent-shaped lacerations on the forehead and scalp, most of

them about one inch long and a half-inch wide; thirty-five body wounds; a

broken nose; eyelids bruised and swollen shut; two upper medial incisors

snapped off; fractured skull plates from the fifteen blows; cracked skull; and

her frontal blows separated; lungs and windpipe were congested with blood, but

with no blood in the stomach, she was unable to swallow suggesting she was

already unconscious; cyanosis in her fingernails; four blows to her left hand

and wrist; a quarter-size bruise on her left shoulder; right little finger

broken; the fingernail on the left ring finger was torn off; "creamy white

exudate" in her vagina; "abundant" amounts of epithelial cells

and bacteria in the vagina; and a four-month gestational male in her uterus. On

her death certificate, Dr. Adelson listed Marilyn's time of death "at

about 4:30 AM" on July 4, 1954 due to massive head injuries, the manner

being homicide.1

|

| Dr. Lester Adelson, Deputy Coroner for Cuyahoga County examines X-Rays of the hands, feet and head of Mrs. Marilyn Sheppard. |

|

| "Death Mask" of the head injuries of Mrs. Marilyn Sheppard. The real death mask resides in the museum of the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner's Office |

|

| Marilyn Sheppard lies dead in her bedroom at her home in Bay Village, Ohio |

The Press Coverage Begins

|

| Mrs. Sam H. Sheppard, an expectant mother, was murder victim in her Bay Village home  |

|

| Samuel H. Sheppard Jr. "Chip" |

|

| Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Sheppard |

|

| Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Sheppard |

|

| Marilyn, Chip, and Sam |

|

| Sam and Marilyn Sheppard wedding day |

|

| Marilyn and Sam water-skiing |

Louis B. Seltzer and the Cleveland Press

Seltzer's

background was the near opposite of Sam Sheppard's. He had grown up

impoverished, the oldest of five, the son of an out-of-work carpenter who tried

to make a living writing dime novels. His mother made his clothes by cutting up

discarded men's suits and shirts. Louis dropped out of sixth grade to work as

an office boy at the Press and fell in love with the thrill of big-city

news-papering during the Front Page Era, when cutthroat competition and

entertainment trumped the need to be responsible civic force. As a police-beat

reporter, he entered apartments and houses to "borrow" photographs

from families of crime victims to splash on page 1, a routine practice.

Firehouses' coded alarms sounded in the newsroom, and he literally ran from the

newsroom to be first on the scene. He witnessed seven electrocutions and took

part in circulation-building stunts, such as using magician Harry Houdini to

obtain evidence in exposing phony spiritualists who were preying on

unsuspecting immigrants. He even got himself locked into the huge, antiquated

Ohio State Penitentiary to expose its brutal conditions. He shot up the ranks

at the Press, the flagship of the

nineteen-paper Scripps Howard chain, and at only thirty years old was named

editor in 1929. By 1939, he was earning seventy-five thousand dollars a year, a

huge salary for an editor, as well as a bonus of 5 percent of any increases in

the Press's operating profits. If the Press did well, so did he,

which gave him a financial incentive to create circulation-boosting crusades.

Seltzer was an astute marketeer; he preached that a newspaper had to connect

with the everyday lives of its readers from womb to tomb. Among his

innovations, his staff sent cards to parents of newborns and invited couples

reaching their fiftieth anniversary to a free banquet. Early in his career as

editor, Seltzer set aside part of each Friday to visit one of Cleveland's

forty-six ethnic neighborhoods with his wife, Marion. Many days he gave two or

three speeches to clubs, women's societies, or church groups, speeding from

address to address, arriving at one for the first course and hitting the other

by dessert. Typically, he was home for an early family dinner at around 4 PM.,

just after the late stock edition hit the streets, then changed suits and hit

the dinner-speech circuit. Clevelanders felt they knew him and trusted him.

They believed his newspaper would tell it like it is. Seltzer ran a loud,

loose, profane newsroom. He encouraged practical jokes. Once he threw a

firecracker under the chair of a reporter interviewing a woman on the

telephone. "What was that!" the startled woman demanded. A

firecracker, the reporter said calmly. "What would Mr. Seltzer think about

that?" she wanted to know. "Ma'am, he's the one who threw it."

By the time of the Sheppard murder, Seltzer was known as "Mr.

Cleveland," the most powerful man in the region, a political kingmaker. He

believed that his newspaper, with information and a loud voice, could solve the

city's problems. The Press was a "fighting paper" that

"fought like hell for the people" he liked to explain. When local

government did not function, the Press struck with editorial might, even

if it meant using the sledgehammer to crush a gnat. Overkill could be

rationalized by it editors because the cause was just, for the little guy.

Anyone who tried to play outside these rules or who was perceived as looking

down on his mostly blue-collar readers, Seltzer enjoyed taking down a peg. The

players in the Sheppard murder were perfect fodder for his audience. The

Sheppard family was affluent, suburban nonveau riche, osteopaths with a hint of

immortality, and they had quickly retained lawyers, one of Seltzer's favorite

editorial targets. Seltzer decided that the Drs. Sheppard, with status and

wealth, were impending a murder investigation and thwarting justice, thereby

mocking the people's will. They needed a comeuppance. For the rest of the

Sheppard murder investigation, Seltzer and Gerber worked together closely, one

creating news, the other inflating it."

Even in Seltzer's autobiography The

Years Were Good, he devoted the entire 26th chapter to the Sheppard murder

case. In the chapter, he attempted to answer the question of why the Press

went "on a killing-spear" one could say about the case.

"It was a calculated

risk-a hazard of the kind which I believed a newspaper sometimes in the

interest of law and order and the community's ultimate safety must take. I was

convinced that a conspiracy existed to defeat the ends of justice, and that it

would affect adversely the whole law-enforcement machinery of the County if it

were permitted to succeed. It could establish a precedent that would destroy

even-handed administration of justice."

Seltzer also acknowledges that The

Press had been applauded and criticized, because of how it "inflamed

public opinion by its persistent and vigorous pounding away at the case."

and that some believed that the Sheppard case had been "tried" in the

press, rather than in the courtroom, and that he would do the same thing over

again. The most noble thing that he did, was that he wrote the editorials

himself, rather then having his staff taking the risk.

The Inquest

|

| Dr. Samuel Gerber, Cuyahoga County Coroner holds an inquest. Dr. Sam Sheppard (right) answers Gerber's questions |

On July 21, 1954, The Press publishes an editorial with the headline

"WHY NO INQUEST? DO IT NOW , DR.

GERBER!" Later in the day, Dr. Gerber announces that he is calling an

inquest that will begin the next day on July 22 at the Normandy High School in

Bay Village. There is heavy media presence at the inquest and the inquest lasts

for three-days.

In his thesis paper, PRESSING

CHARGES: The Impact of the Sam Sheppard Trials on Courtroom Coverage and

Criminal Law, Tali Yahalom quotes The Press' Bill Tanner about the

inquest for the Sheppard case. Tanner admits that, "If it hadn't been for

the newspaper urging this, it probably wouldn't have happened."

|

| Mug Shot of Sam Sheppard August 2, 1954 |

The Trails

The media coverage of Marilyn Sheppard's murder only gets worse, and the Cleveland

Press and Louis B. Seltzer continues to slaughter all involved parties of

the case. His "editorials" scream of justice for Marilyn and continue

to demand action in solving this brutal crime. After the Press runs an

editorial asking why Sam Sheppard isn't in jail, Sam is arrested at the home of

his parents. That would be the last time in ten years that Sam Sheppard would

be a free man.

|

| The Jury visits The Sheppard's Bay Village home |

The start of the 1964 murder trail of Marilyn Sheppard is a nightmare the

moment it begins. Despite the case having already been covered extensively in

the newspapers, the judge never sequesters the jury and their names, addresses

and faces are printed countless times in the press. When asked numerous times

for the case to be ruled a mistrial or to be thrown out because of the 'circus

like' manner the court room is being run, Judge Edward Blythin refuses and on

November 3, 1954, the murder trial of Marilyn Sheppard begins with a visit to

the Sheppard's home with the jury, Dr. Sheppard himself and of course, the

media. It is not until December 17, 1954, a little over a month after the

trial started that the jury on the case finds themselves sequestered for the

first time, but by then the damage is done. Sam Sheppard has been denied his

right of a fair trial due to the media coverage. On December 21, 1954 Dr.

Samuel Holmes Sheppard is found guilty of murder in the second degree.

|

| Dr. Sam Sheppard, now a free man with his son Chip and 2nd wife Ariane Tebbenjohanns |

Appeals for a new trial begin almost immediately and every time, Sam is

denied his sixth amendment. For the next ten years, Sam Sheppard remains

behind bars in a maximum security prison near Columbus until defense lawyer F.

Lee Bailey files a petition for habeas corpus in federal court on April 13,

1963. In his petition, Bailey argues, among other things, that prejudicial

publicity in the trial violated Sam's right to due process. On July 15 and 16,

1964 Judge Weinman tosses out Sheppard's conviction on what he calls

"constitutional grounds" calling his trial a "mockery of

justice." For the first time in ten years, Sam Sheppard is released from

prison on $10,000 bond and marries Ariane Tebbenjohanns.

Between October 8, 1964 and March 4, 1965 the Sixth Circuit Court of

Appeals in Cleveland hears the state's appeal of Judge Weinman's decision and

on a 2 to 1 vote, the decision is reversed. Sam is allowed to remain free on

bail pending his appeal to the United States Supreme Court.

|

| Sam Sheppard with F. Lee Bailey |

On February 28, 1966, the United States Supreme Court begins to hear oral

arguments for Sheppard V. Maxwell. Sheppard is represented by attorney

F. Lee Bailey. The state is represented by Ohio Attorney General William Saxbe.

On June 6, 1966, almost twelve years after the murder of Marilyn Sheppard, the

Supreme Court reverses Sam's murder conviction on due process grounds on an 8

to 1 vote. They cite "virulent publicity" which might have affected

the jury's verdict.

On October 24, 1966, now twelve years after a jury hears the

murder trail of Marilyn Sheppard, Cuyahoga County Common Pleas judge Francis

Talty is assigned to hear the second murder case against Sam Sheppard.

Determined to avoid another 'Circus Trial' Judge Talty laid down the

following rules in his court room:

- 1. There were to be no cameras on the premises of the court building and not even sketch-makers in the courtroom. No press table inside the bar. No room for radio equipment. No freedom to move about the courtroom-nobody could leave or enter while court was in session. No statements to the press by lawyers or witnesses.

- 2. The number of benches for spectators and reporters were cut down to three totally 42 seats, which were assigned to the media. There were four for the two Cleveland newspapers, the Plain Dealer and the Press; eight for local radio and TV stations and one each for the AP and UPI. There were none for out-of-town newspapers, for national publications or for television networks.

Naturally, the media was upset at this order, but after the Supreme

Court ruling, they weren't about to challenge this.

|

| Dr. Sam Sheppard and third wife Colleen Strickland |

Unlike the first case, the seven men, five women and three alternates were

sequestered in a downtown hotel. Phone calls home would be monitored and their

only news would come from newspapers that had been clipped of the Sheppard

case.

On Friday, November 16, 1966, just shy of a month after the trial started

it was over. At 9:30 PM that evening Judge Talty read Sam Sheppard his

verdict-"We the jury impaneled in the above case find the defendant not

guilty." It was music to Sam's ears, provided that he actually heard the

verdict. By now, the toll of Marilyn's murder and three trials had drove the

once promising physician to booze and pills. His family had been destroyed.

Both his parents and Marilyn's father were dead, and he was on to wife number

three.

|

| The Cleveland Press headline for April 6, 1970 |

|

| "The Killer" |

|

| Knollwood Cemetery- The final resting place for Sam and Marilyn |

|

| The crypt for Sam and Marilyn Sheppard and their unborn son |

Disgraced Journalist?

Is Louis B. Seltzer a disgraced journalist? Personally, I'm in favor

of labeling him one. However, there are people who lived through the era of

Seltzer that would swear his the best thing since sliced bread. A disgraced

journalist is one who makes up stories like Stephen Glass or Piers Morgan, but

Seltzer never officially got caught making up stories. Instead, the countless

headlines that splashed upon Page 1 of Cleveland Press were editorials

wrote by the editor of the paper. Still considered a disgrace? In my mind, you

bet. What saved him from falling under the 'made up stories' was that one

little word-editorial. He could claim if ever questioned that it was his own

opinion.

|

| Headlines, like the one above, saying SOMEBODY IS GETTING AWAY WITH MURDER flooded The Cleveland Press when Louis Seltzer determined that nothing was being done |

But this was not the first case that Seltzer's beloved Cleveland Press

went out on a limb regarding headlines in their papers. In John Bellamy's book The

Maniac in the Bushes, clippings from the Press during the Torso

"Kingsbury Run" Murders feature such headlines such as GHOSTLY HAND SEEN IN LAKE , BONES ON SHORE DISAPPEAR which cause numerous phone

calls and tips into the police about false sightings and/or useless discovers

in the case. Better yet, other headlines that splashed across Press's

papers included POLICE SEEKING THRILL SLAYERS, a story they "got from

unnamed police officers" and yet another "editorial" titled

MADMAN OR COOL KILLER? POLICE PROBERS GROPING FOR LEADS IN COUNTY'S FIVE HEADLESS MURDERS." In 1937, BABY FARM IS TORSO DEATH CLEW, a fact that was never proven because the baby farm

referred to in the story didn't exist.

Is Seltzer a disgraced journalist? Yes. He singlehandedly destroyed a man

in the newspaper of Cleveland. Did he make up stories? Most likely, but then

covered his trail with calling them editorials. Why did he lead the Cleveland

Press into this? Seltzer called it justice. Doris O'Donnell, a reporter for

Cleveland News said that "When Louise Seltzer spoke, politicians

shook. [He was a] little guy [but] the king of journalism." Even Seltzer

himself admitted in his autobiography, "There were risks both ways. One

represented a risk to the community. The other was a risk to The Press. We

chose the risk to ourselves. As Editor of The Press I would do the same thing

over again under the same circumstances."

You be the judge about this one.

Epilogue

The Sam Sheppard murder case remains unsolved to this day. Marilyn and Sam's only son, Chip, continues to try and clear his father's name and find the real murder of his mother's death.

But, take this into consideration. If Seltzer wasn't a 'disgraced journalist' who singlehandedly led his paper into a witch hunt of the century with this case with all the headlines run and other comments made in the paper, would the Supreme Court of this great nation really have to vote 8 to 1 that Dr. Samuel Sheppard, a fine physician until the untimely death of his young, pregnant wife, that Sheppard didn't get a fair trail because of the media circus that had covered the case almost from the very moment it started? I doubt it. But hey, that's just my opinion...or as Seltzer would write it-An Editorial